Does the absolute size of a country matter for public transport planning? Usually it does not – construction costs do not seem to be sensitive to absolute size, and the basics of rail planning do not either. That Europe’s most intensely used mainline rail networks are those of Switzerland and the Netherlands, two geographically small countries, is not really about the inherent benefits of small size, but about the fact that most countries in Europe are small, so we should expect the very best as well as the very worst to be small.

But now Germany is copying Swiss and Dutch ideas of nationally integrated rail planning, in a way that showcases where size does matter. For decades Switzerland has had a national clockface schedule in which all trains are coordinated for maximum convenience of interchange between trains at key stations. For example, at Zurich, trains regularly arrive just before :00 and :30 every hour and leave just after, so passengers can connect with minimum wait. Germany is planning to implement the same scheme by 2030 but on a much bigger scale, dubbed Deutschlandtakt. This plan is for the most part good, but has some serious problems that come from overlearning from small countries rather than from similar-size France.

In accordance with best industry practices, there is integration of infrastructure and timetable planning. I encourage readers to go to the Ministry of Transport (BMVI) and look at some line maps – there are links to line maps by region as well as a national map for intercity trains. The intercity train map is especially instructive when it comes to scale-variance: it features multihour trips that would be a lot shorter if Germany made a serious attempt to build high-speed rail like France.

Before I go on and give details, I want to make a caveat: Germany is not the United States. BMVI makes a lot of errors in planning and Deutsche Bahn is plagued by delays; these are still basically professional organizations, unlike the American amateur hour of federal and state transportation departments, Amtrak, and sundry officials who are not even aware Germany has regional trains. As in London and Paris, the decisions here are defensible, just often incorrect.

Run as fast as necessary

Switzerland has no high-speed rail. It plans rail infrastructure using the maxim, run trains as fast as necessary, not as fast as possible. Zurich, Basel, and Bern are around 100 km from one another by rail, so the federal government invested in speeding up the trains so as to serve each city pair in just less than an hour. At the time of this writing, Zurich-Bern is 56 minutes one-way and the other two pairs are 53 each. Trains run twice an hour, leaving each of these three cities a little after :00 and :30 and and arriving a little before, enabling passengers to connect to onward trains nationwide.

There is little benefit in speeding up Switzerland’s domestic trains further. If SBB increases the average speed to 140 km/h, comparable to the fastest legacy lines in Sweden and Britain, it will be able to reduce trip times to about 42 minutes. Direct passengers would benefit from faster trips, but interchange passengers would simply trade 10 minutes on a moving train for 10 minutes waiting for a connection. Moreover, drivers would trade 10 minutes working on a moving train for 10 minutes of turnaround, and the equipment itself would simply idle 10 minutes longer as well, and thus there would not be any savings in operating costs. A speedup can only fit into the national takt schedule if trains connect each city pair in just less than half an hour, but that would require average speeds near the high end of European high-speed rail, which are only achieved with hundreds of kilometers of nonstop 300 km/h running.

Instead of investing in high-speed rail like France, Switzerland incrementally invests in various interregional and intercity rail connections in order to improve the national takt. To oversimplify a complex situation, if a city pair is connected in 1:10, Switzerland will invest in reducing it to 55 minutes, in order to allow trains to fit into the hourly takt. This may involve high average speeds, depending on the length of the link. Bern is farther from Zurich and Basel than Zurich and Basel are from each other, so in 1996-2004, SBB built a 200 km/h line between Bern and Olten; it has more than 200 trains per day of various speed classes, so in 2007 it became the first railroad in the world to be equipped with ETCS Level 2 signaling.

With this systemwide thinking, Switzerland has built Europe’s strongest rail network by passenger traffic density, punctuality, and mode share. It is this approach that Germany seeks to imitate. Thus, the Deutschlandtakt sets up control cities served by trains on a clockface schedule every 30 minutes or every hour. For example, Erfurt is to have four trains per hour, two arriving just before :30 and leaving just after and two arriving just before :00 and leaving just after; passengers can transfer in all directions, going north toward Berlin via either Leipzig or Halle, south toward Munich, or west toward Frankfurt.

Flight-level zero airlines

Richard Mlynarik likes to mock the idea of high-speed rail as conceived in California as a flight-level zero airline. The mockery is about a bunch of features that imitate airlines even when they are inappropriate for trains. The TGV network has many flight-level zero airline features: tickets are sold using an opaque yield management system; trains mostly run nonstop between cities, so for example Paris-Marseille trains do not stop at Lyon and Paris-Lyon trains do not continue to Marseille; frequency is haphazard; transfers to regional trains are sporadic, and occasionally (as at Nice) TGVs are timed to just miss regional connections.

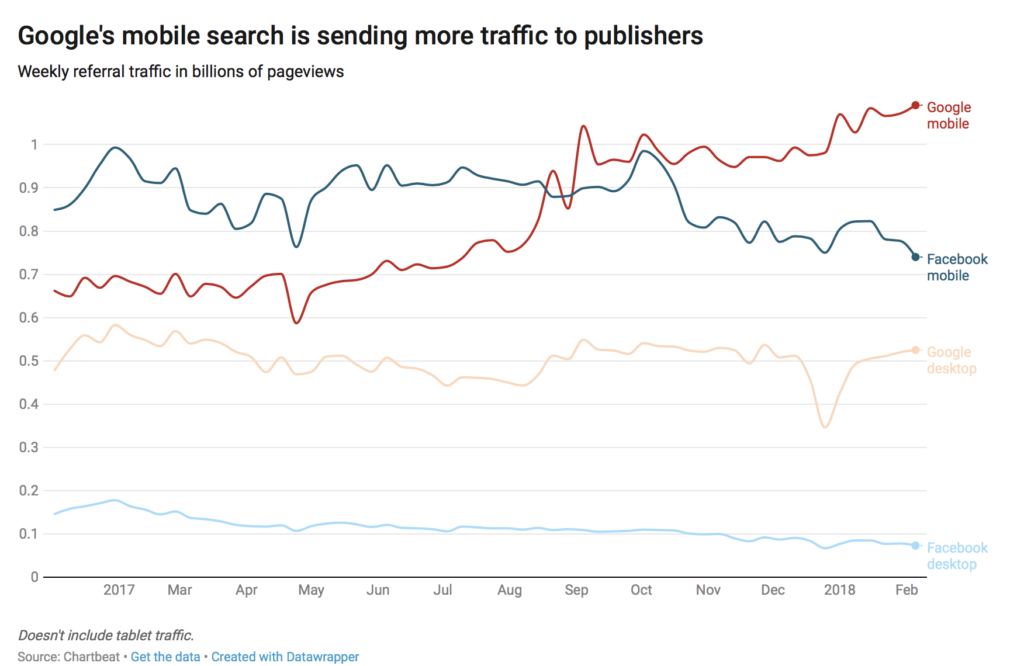

And yet, with all of these bad features, SNCF has higher long-distance ridership than DB, because at the end of the day the TGVs connect most major French cities to Paris at an average speed in the 200-250 km/h range, whereas the fastest German intercity trains average about 170 and most are in the 120-150 range. The ICE network in Germany is not conceived as complete lines between pairs of cities, but rather as a series of bypasses around bottlenecks or slow sections, some with a maximum speed of 250 and some with a maximum speed of 300. For example, between Berlin and Munich, only the segments between Ingolstadt and Nuremberg and between Halle and north of Bamberg are on new 300 km/h lines, and the rest are on upgraded legacy track.

Even though the maximum speed on some connections in Germany is the same as in France, there are long slow segments on urban approaches, even in cities with ample space for bypass tracks, like Berlin. The LGV Sud-Est diverges from the classical line 9 kilometers outside Paris and permits 270 km/h 20 kilometers out; on its way between Paris and Lyon, the TGV spends practically the entire way running at 270-300 km/h. No high-speed lines get this close to Berlin or Munich, even though in both cities, the built-up urban area gives way to farms within 15-20 kilometers of the train station.

The importance of absolute size

Switzerland and the Netherlands make do with very little high-speed rail. Large-scale speedups are of limited use in both countries, Switzerland because of the difficulty of getting Zurich-Basel trip times below half an hour and the Netherlands because all of its major cities are within regional rail distance of one another.

But Germany is much bigger. Today, ICE trains go between Berlin and Munich, a distance of about 600 kilometers, in just less than four hours. The Deutschlandtakt plan calls for a few minutes’ speedup to 3:49. At TGV speed, trains would run about an hour faster, which would fit well with timed transfers at both ends. Erfurt is somewhat to the north of the midpoint, but could still keep a timed transfer between trains to Munich, Frankfurt, and Berlin if everything were sped up.

Elsewhere, DB is currently investing in improving the line between Stuttgart and Munich. Trains today run on curvy track, taking about 2:13 to do 250 km. There are plans to build 250 km/h high-speed rail for part of the way, targeting a trip time of 1:30; the Deutschlandtakt map is somewhat less ambitious, calling for 1:36, with much of the speedup coming from Stuttgart21 making the intercity approach to Stuttgart much easier. But with a straight line distance of 200 km, even passing via Ulm and Augsburg, trains could do this trip in less than an hour at TGV speeds, which would fit well into a national takt as well. No timed transfers are planned at Augsburg or Ulm. The Baden-Württemberg map even shows regional trains (in blue) at Augsburg timed to just miss the intercity trains to Munich. Likewise, the Bavaria map shows regional trains at Ulm timed to just miss the intercity trains to Stuttgart.

The same principle applies elsewhere in Germany. The Deutschlandtakt tightly fits trains between Munich and Frankfurt, doing the trip in 2:43 via Stuttgart or 2:46 via Nuremberg. But getting Munich-Stuttgart to just under an hour, together with Stuttgart21 and a planned bypass of the congested Frankfurt-Mannheim mainline, would get Munich-Frankfurt to around two hours flat. Via Nuremberg, a new line to Frankfurt could connect Munich and Frankfurt in about an hour and a half at TGV speed; even allowing for some loose scheduling and extra stops like Würzburg, it can be done in 1:46 instead of 2:46, which fits into the same integrated plan at the two ends.

The value of a tightly integrated schedule is at its highest on regional rail networks, on which trains run hourly or half-hourly and have one-way trip times of half an hour to two hours. On metro networks the value is much lower, partly because passengers can make untimed transfers if trains come every five minutes, and partly because when the trains come every five minutes and a one-way trip takes 40 minutes, there are so many trains circulating at once that the run-as-fast-as-necessary principle makes the difference between 17 and 18 trainsets rather than that between two and three. In a large country in which trains run hourly or half-hourly and take several hours to connect major cities, timed transfers remain valuable, but running as fast as necessary is less useful than in Switzerland.

The way forward for Germany

Germany needs to synthesize the two different rail paradigms of its neighbors – the integrated timetables of Switzerland and the Netherlands, and the high-speed rail network of France.

High investment levels in rail transport are of particular importance in Germany. For too long, planning in Germany has assumed the country would be demographically stagnant, even declining. There is less justification for investment in infrastructure in a country with the population growth rate of Italy or of last decade’s Germany than in one with the population growth rate of France, let alone one with that of Australia or Canada. However, the combination of refugee resettlement and a very strong economy attracting European and non-European work migration is changing this calculation. Even as the Ruhr and the former East Germany depopulate, we see strong population growth in the rich cities of the south and southwest as well as in Berlin.

The increased concentration of German population in the big cities also tilts the best planning in favor of the metropolitan-centric paradigm of France. Fast trains between Berlin, Frankfurt, and Munich gain value if these three cities grow in population whereas the smaller towns between them that the trains would bypass do not.

The Deutschlandtakt’s fundamental idea of a national integrated timed transfer schedule is good. However, a country the size and complexity of Germany needs to go beyond imitating what works in Switzerland and the Netherlands, and innovate in adapting best practices for its particular situation. People keep flying domestically since the trains take too long, or they take buses if the trains are too expensive and not much faster. Domestic flights are not a real factor in the Netherlands, and barely at all in Switzerland; in Germany they are, so trains must compete with them as well as with flexible but slow cars.

The fact that Germany already has a functional passenger rail network argues in favor of more aggressive investment in high-speed rail. The United States should probably do more than just copy Switzerland, but with nonexistent intercity rail outside the Northeast Corridor and planners who barely know that Switzerland has trains, it should imitate rather than innovating. Germany has professional planners who know exactly how Germany falls short of its neighbors, and will be leaving too many benefits on the table if it decides that an average speed of about 150 km/h is good enough.

Germany can and should demand more: BMVI should enact a program with a budget in the tens of billions of euros to develop high-speed rail averaging 200-250 km/h connecting all of its major cities, and redo the Deutschlandtakt plans in support of such a network. Wedding French success in high-speed rail and Swiss and Dutch success in systemwide rail integration requires some innovative planning, but Germany is capable of it and should lead in infrastructure construction.